Once Upon Our Time

Explore new worlds, from Greek myths retold, to philosophy, to suspenseful stories, to fantasy. Sarah covers everything from current topics, to poetry, to other worlds of fiction. It will blow your mind. It will mindstorm.

Explore new worlds, from Greek myths retold, to philosophy, to suspenseful stories, to fantasy. Sarah covers everything from current topics, to poetry, to other worlds of fiction. It will blow your mind. It will mindstorm.

"Acropolis of Athens" by Leo von Klenze, 1846

Athens, the glorious city that became the centre for Greek art, drama, and philosophy, was not always the great power that was home to Socrates. Long before its Golden Age, it started off in a very modest way, with a small population, and the story of its founding places it at the very heart of Greek civilisation. Allow me to regale you with a marvellous origin tale.

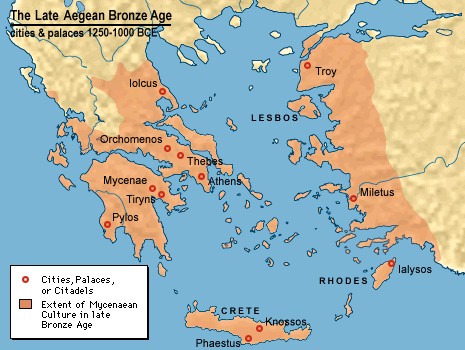

Athens on a Bronze Age map

There was a small town near ocean front, on the southern part of the Greek mainland, that was known as "Kekropia." It was essentially a citadel fortress, growing in prosperity, but to achieve true greatness, it needed the blessing of the Gods. What it needed was a protector, a God with whom the city would be identified. The Gods may be wise and virtuous, but they are certainly not too modest when it comes to appealing to their vanity. Mortals who knew their place and revered the Gods would always prosper.

King Kekrops, founder of Athens

who was said to have taught them

about marriage, how to read and write, and to bury their dead

The citizens of Kekropia, having originally named their town after Kekrops, the ruler of the elevated area that was the Akropolis, or "high city," let word be carried forth that they sought the protection of the God that would forever have its name associated with this place, a place that would worship this divinity and live by its values. It would be a great honour for the Kekropians and one that would shape their civilsation and their values.

The Gods of Mt. Olympus

With a larger city, no doubt most of the Greek Pantheon (the twelve Gods of Mt. Olympus) would have presented itself, but given the modesty of this place, there were only two Gods who presented themselves to win over the favour of these mortals. Poseidon, emerging from the sea, struck down his mighty trident upon the Earth, just outside the town, and suddenly, a source of water sprang forth. This may sound like the kind of gift a town would need, but unfortunately, because Poseidon was the God of the Sea, this water was salt water, so it was not useful for drinking, merely an attractive feature. Given that the actual ocean was not too far off either, this was not of much use to the Kekropians.

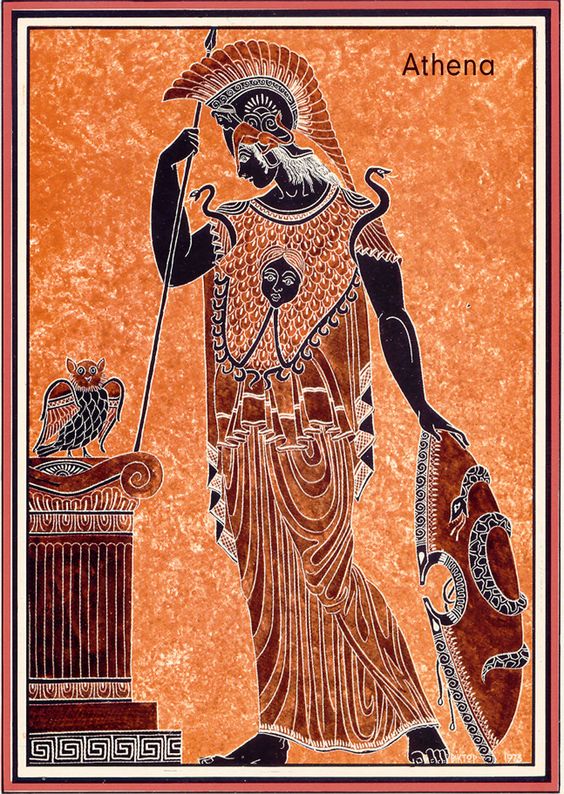

Athena

The second deity was Athena, Goddess of Wisdom and of Defensive Warfare. By her divine powers, she caused a new type of tree to spring forth, the olive tree. This was a magnificent gift, for the Greeks would come to use olive oil for so many things. It was not just used for cooking; it was also used in sacred rites, including at the Olympics, and used heavily in medicine, as advocated by Hippocrates, after whom the Hippocratic Oath is named. It was also used to style hair and treat skin, long before we had lotion. It was so useful that it was nicknamed "liquid gold" due to its immense value, while being very cheap to produce.

Poseidon and Athena in competition,

with the olive tree having been created

Indeed, the olive tree itself became a symbol for Athena herself, and when the Romans took basically copied the Greek Gods, she became Minerva to them, and since Athena was associted with Greek civilisation, this deity became a symbol of agriculture and the value of the olive tree, equally important to the Romans. Minerva would not be as great a deity as Athena, but she is still remembered among their deities and her gifts mean abundance.

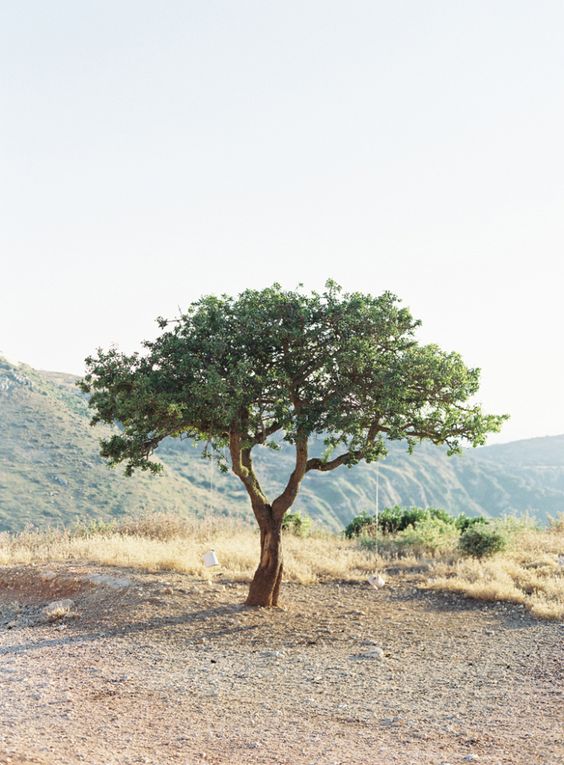

The olive tree

In honour of this fantastic gift from Athena, the city renamed itself "Athens" in her honour. She took the role as the city's main protectress. It would be a city famed for its wisdom, its philosophers, and its literature. It would come to represent the best that Greece had to offer and eventually be its centre of power too. And it all began with the gift of the olive tree, the gift that keeps on giving still today.

When I speak of my love for freedom and natural rights, there is one concern that I am frequently met with, namely, that of weapons of mass destruction. It's all good and well to defend the right of citizens to bear arms, and to point out that banning particular numbers of magazines or semi-automatic firing capacity has never, not even once, made the streets more safe, but less so, since it only made the criminals wealthier and more influential. That's the typical Conservative argument, after all: less regulation from the State. But surely, even if "common sense regulation" is typically code for a bad law, we have to have some restrictions in terms of who can own what?

Let's jump in with the most eye-grabbing of all examples: the nuclear bomb. Surely am I not suggesting that just anyone should be allowed to own or make a nuclear bomb? Actually, that is exactly going to be my point. Yes, every single individual on this Earth has that right and it should not be legally restricted at all. Now, this may shock you to hear, especially you already know that I, of all people, am so strongly opposed to war, as well as to nuclear weapons. Wouldn't this mean an uncontrolled escalation of nuclear arms, just bombs going off everywhere, with a total nuclear winter?

We are all familiar with the scare tactic arguments. We know the fear. There is good cause why we fear nuclear weapons and why we fear them far more than guns. Guns can't wipe out humanity but nuclear weapons can, and furthermore, it wouldn't even take that much in terms of foolish decisions. So why would I not be in favour of restricting that right? It seems reasonable enough; I give up my right to own nuclear arms and in exchange, humanity does not get destroyed.

Well, let's examine it. Every country in the world outlaws nuclear arms for private citizens, so we are already in that reality; it is not a hypothesis. Did we move beyond nuclear arms and towards peace? No, we have constant conflicts and we have more nuclear arms than ever, and leaders are still flirting more with their use than promoting peace talks. Not only that, but a huge number of them are not being carefully contained, so they risk detonating by sheer bad luck, similar to how Chernobyl was neglected. So why did they proliferate like this?

It's quite simple; it's because the State has a monopoly on these arms. We cannot own them but the State can build them because it gives itself permission and it takes whatever funds it deems necessary from us to do so. A private citizen would have to invest his own money and it would have to seem necessary. Why would a private citizen build a nuclear bomb? What could he gain of value by doing so? He would have to see the possibility of gaining more than he lost by investing his resources into building one. After all, he makes himself a very easy target, whereas a diffused class of State government, existing everywhere, is far more difficult to get to.

To answer that question, we have to ask why they are built in the first place. It's clearly not a weapon used in any kind of defence; there is only one case where it was actually deployed in war and that was during the Second World War, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, and it was alleged at the time that it was a payback for the invasion of Pearl Harbor. However, the historical evidence shows us something quite different; America had invaded Japanese territory and attacked their ships before Pearl Harbor, so it was not a payback at all; it was pure offensive warfare by a warfare State.

All of these were State actions. The U.S. government was willing to kill thousands upon thousands of innocent civilians just to establish its power (Pearl Harbor, by contrast, was intended to destroy military vessels and killed mostly troops) and influence and it worked. It also made sure the truth about this attack was hidden from public view by State censorship, and even today, few know the truth. All of this would go away if we all could build nuclear arms. A private person could not hide it, or threaten anyone with an entire army if his intentions were called out, and if by some dark miracle he managed to do it, his actions would be known to all.

There is deterrence not in arms but in private ownership of arms. If I don't know who has a gun, I am far less likely to attack them in the street. In fact, the most peaceful time in America was the time of the fictional Wild West, which we think we know because of very entertaining Hollywood movies, but movies which were actually influenced largely by Progressive writers wanting to depict said times as being lawless in the sense of chaotic with criminals ruling everywhere and there needing to be a strong person to bring about order. This does appeal to all of us but there was a hidden motive, namely to defend the idea of a growing State power.

"Okay," you might protest, "but I thought we were talking nuclear arms?" Well, we are. The same principle applies. Deterrence in nuclear arms is not in one State having them and another one also having them, but in private individuals being able to have them. We can keep check on private individuals, far better than we can the State. The State can buy and build as many as it wants and sacrifice its citizens, just like it does during war. However, a private warlord is not going to see this as a winning endeavour. He would spend all his resources building something that would ruin all his gains, and his followers would not want to stay with him, particularly since he has made them a huge target, along with himself. A private warlord, unlike the State, cannot compel his followers by the use of the legal system and the use of nationalised forces, like the police or the military.

This is where you might find yourself resisting. Didn't Osama Bin Ladin essentially do this? He didn't use nuclear arms, but he convinced his followers to commit suicide in attacking America. Wouldn't the world I describe be a world of a thousand Bin Ladins, all with nuclear arms? To answer this, we have to understand why he attacked what was actually two buildings in America, not the country itself. It was a symbol, yes, but it was part of the land the government claims to rule over, and the government dictated it was an attack upon all of America, the very thing Osama wanted. If these had been privately owned buildings in a geographic area that was not under a government, such an attack would most likely never have been carried out, because those buildings would have no connection to a government that had killed millions of people in the Middle East. If there is nothing to be gained by attacking just buildings, rather than a country as a whole, then there is no cause to think he would go even farther and waste all of his resources to build nuclear bombs to do the same.

The same principle applies as in the case with the gun. If I don't know if a neighbouring town has a nuclear bomb, I am far less likely to go in to ransack it, as a warlord. As for abusing this privilege, who has abused it? Not private citizens, not even once; only governments did that. Governments? Didn't I say there was only one attack? Well, yes, but plenty of abuse. America, the United Kingdom, and France all carried out nuclear "tests" regularly for decades, just exploding and ruining landscapes. Why? Well, they ruled over them, and they didn't live there, so why not? A private individual proposing the same can't escape that because he does not have dominion over others' territory. He would have to buy his own territory, a vast one at that, and completely destroy it. Why would he destroy his own territory? Good question. He wouldn't. You only do that in an area where it doesn't affect you, for obvious reasons. If you can only do it in your own private property, you are far less likely to do it.

There is only one pin left to be knocked down. What about proliferation? You may concede that more guns actually produces more safety, but surely we don't want more nuclear bombs? If we allow it legally, won't the number of nuclear arms just explode, pun intended? We have to look at why we have so many to begin with and again, all of it stems from the fact that the State is using someone else's money and is never held responsible for its actions because it has a monopoly on law and justice.

A private citizen has to spend his own money, to start with, which not only greatly limits the number of who can do it, but also the number deciding to invest thus because he will be subject not only to criticism but to intervention by anyone seeing it as self-defence. After all, I can defend myself against a robber using a gun, so if I see someone building a bomb, I have the same right to intervene. By contrast, police cannot stop the State from building more bombs; it will instead arrest the people who would stop them from doing so.

This private person can only build and maintain it on their own property, which they are far more likely to use responsibly, which we know is the case of any private vs. public property. We all see how all public property falls apart due to neglect (as well as vandalism leading to more neglect), as are literally thousands of nuclear arms right now. A privately owned arm would be better maintained, more responsibly, because it reflects on the owner, and that owner would have to convince people around him, entire regions of people, that they are not at risk. It's not like it is built overnight, either, so it would take a lot of convincing for any people to allow it. Only those truly considered trustworthy would not have their work impeded, which would be a tiny number indeed, and this is a far better check on their potential abuse.

In addition, there are no spoils of war for private individuals using a nuclear arm. A State can use it because it wants to rule over the other population and they don't care how many die or how devastated the region is; it only needs submission and to get its desired, stolen resources from elsewhere, not in the affected area. It doesn't even have to extract resources from neighbouring territories; it already has all the funds it needs and it just wants control. A private warlord would need to govern more sagely or his own supply would vanish into thin air. Even from a practical viewpoint, we have to admit only a State has an interest in simply growing the number of nuclear arms. For a private citizen, it would hardly ever be worth investing in because there is no scenario where one would gain more than one loses.

But isn't this assuming everyone is ultimately rational? It may be good for the majority of people who are governed by reason, but what about the crazy people? A small number of crazy people could just explode them and kill of humanity. Well, the craziest psychopaths already made their way into government and did their worst. We would take away their power to do wrong by allowing everyone to have their natural rights. Again, if a crazy person is ready to kill everyone, that person can be easily spotted and far more easily stopped without the protection of the State, and furthermore, he is far less likely to be gifted enough to make enough money to develop his own nuclear arms and convince everyone that he is not a danger. Government people are gifted at playacting, not at actually making money. The private citizen, by contrast, can't just make up a lie about the people having been attacked by terrorists already because he does not have control over State media that gives them a false version of history.

If someone makes it past all of these check points, then how would a State monopoly help us? The idea is that we would create greater safety by making sure it falls under the exclusive dominion of the State. Well, as we have already seen, not only does that not stop the crazy people, but it actually vests many of them with a power that makes it easier for them to proliferate nuclear arms and makes it possible for only their propaganda to become official State-approved history. The State is not stopping private people from building nuclear bombs in their basement because virtually no one wants to. There is nothing to be gained there. However, a State can sacrifice as many people as it wants because its resources come by theft. It doesn't even have to give a really convincing story for its construction or use of nuclear weapons; it can just arrest people. A private citizen can't do that, but would have to rely on actual reasons that are solid enough to convince everyone around him that it is totally safe and peaceful.

We're fearing a scenario for which there is no basis. Fearing nuclear winter is a proper fear. However, it is far more likely to be the State that gets us there. Weapons of mass destruction were used far more responsibly before the State established its monopoly over it. As for the irresponsible, better to have them around a people they cannot govern through the use of coercion and force. That is a far better check on their worst instincts and will be far more likely to lead to peace through nuclear disarmament.

There was a time, long before human memory, when everything that we know, was not. Neither the Depths of the Underworld Kingdom, fiercely guarded by the Gods of the Underworld, nor the Celestial Heights of the Aether which the Sky Father and the Sun Mother occupy, existed at all. There was simply Chaos, the Primordial Mover, and the Conflux of the Four Elements: Earth, Water, Air, and Fire, constantly crashing into each other and sparking temporary creations filled with energy that dissipated.

But out of this Chaos came the first order of what we call "Gods," which were the immortal shapers of these forces, birthed out of Chaos, but so powerful that its forces could not undo their life force. They were the Immortals, having absorbed chaotic energy within their life essence and they were able to use it to shape the Cosmos to come. Each one found his or her specialty depending on the Element most present within them.

The first Order shaped the Elements themselves so that the Four Elements were layered in proper succession to bring order to Life, and thus came about the place where we all live and draw breath. The Earth was placed first, able to support the life to come, and much growing from it, whence would spring both men and giants alike as children of Erdos, the God whose dominion included everything on or near the Earth's surface.

As Fire was placed above, providing warmth and the heat of the volcanoes, as well as extending the reach of the Sun Mother. Then Water was placed on top, giving us oceans and all manner of life forms, as well as making the Earth fecund, with the touch of Hydrana, the Goddess of the Ocean. Finally, the Air came on top, providing the dominion of Aethros, the Sky Father, the highest realm of which would be named the "Aether," in his honour, where he makes his home, along with others of his kin.

As Life grew abundant upon the Earth, the Gods fought amongst themselves, for those who favoured the creation of this new Life, which rises and perishes as the waves of the ocean, and who were enamoured with the idea of creation and reshaping Chaos into temporarily stable forms, they were opposed by those who saw this as an intrusion into the perfect never-ending flow of Chaos, never stopping in one form or another, except in the Gods themselves.

The Gods of Order and the Gods of Chaos clashed violently for millennia, until a truce was obtained. The Gods of Order would have their little paradise of creation, but in the end, all must meet with Chaos and be ended. None but the Gods lived forever. With this, they agreed finally, and the Gods of Order set upon creating guardians that would watch over the Earth and help shape the forces of Chaos into forms that pleased them.

The Gods of Order wished above all to see not just life thriving, but a life form akin to their own, gifted with the spirit of higher thinking, who could settle the Earth and bring about new creations, ones the Gods themselves had not thought of. To bring this about, the elemental layers would need their own guardians, to keep each element thriving in its ability to keep creating and sustaining life. As the breath of creation was gifted to the First Men, the Gods birthed their own guardians for our world.

Many children were birthed of the Gods that were not undying, but gifted with immense power of mind and life force. Those Gods who were predominantly fused with a single element gave birth to a species who would be the guardians of one element only, composed solely of that matter. These were the Elementals, containing the essence of Earth, of Fire, of Water, or of Air, powerful sources of magic and guardians of their realm alone.

The Gods who contained multiple elements gave birth to a second species of guardians, containing a balance of all four elements, and these were the dragons. They had the fierce and solid forms of the Earth, along with a love for its precious contents, including the metals buried deep inside it. They had the powers of Fire, able to project it from within themselves, and were not harmed by its touch. They had the gifts of Air, able to travel through it as easily as a tiny bird, their wings powered by the Aether. They had the strength given by Water, swimming as ably as the fish, spawning their eggs in it and sustaining themselves by it, as we do.

In addition, because they were creatures containing the clash of the elements within themselves, not being Gods themselves, they were gifted with an immensely powerful hide that would protect them from the clashes of the Conflux within them. They hardened into immense scales, near impossible for mortal man to penetrate, but they were really there to keep the immense elemental powers within in check.

As Elementals guarded and sustained the elements, so Dragons became the guardians that traversed them, not limited to a single one, and thus, they would be the ones consulted by mankind. Their strength and wisdom was undeniable. However, not all were content to remain as simple guardians and helpers. Over time, some would find themselves despising the weakness of the mortals they were meant to help and gradually, they shifted into the Dragons of Chaos.

For each element, there was one breed of dragon, depending on what element was dominant within it. The Dragons of Order were wise and powerful, but the wisest of all was the Cloud Dragon, fused not only with the Air, but with the gifts of the Aether and the insight of the Gods, able to lead other dragons with its insights and what it gathered from on high, semi-transparent in its appearance. The Pyre Dragon, fabled in many stories as the most fierce fire breather of them all and gifted with a powerful, burning gaze and a blazing, red hide, would aid in many battles against tyrants and other monsters.

The Earth would get much help from the Bronze Dragon, adapted to dark places with excellent night vision, though its clear love for gold and other precious metals would sometimes lead it to become a hoarder. Woe betide the greedy mortal who sets his foot upon its lair to loot it, but its counsel of all things below the Earth was much sought after. Finally, the Thalassic Dragon, with its rippling, blue body, would be a welcome sigh to any sailors needing a blessing on their journey, or help against a sea monster, ready to attack them.

The Dragons of Chaos had darker, more destructive minds. The Ice Dragon, with which the Nordmen are only too familiar, was fuelled by water, in its frozen form, and made that its weapon, turning many into frozen statues. The Black Dragon, plaguing the lands down South, drew its powers from the Earth to gather huge amounts of venom to spit at its enemies, burning like acid. The Mist Dragon, fuelled by Air, projected poisonous gas on which to choke the living around it, and was even able to turn into mist and travel through solid objects. Finally, the Lightning Dragon transformed the gift of Fire into bolts of lightning with which to burn mortals to a crisp, filling the skies with its incendiary lights.

Hear ye and fear ye the dragons. Their kin was brought here to guide us, and seekm them we mortals may, but make sure first of all that it is the right kind, and that you approach it with due deference. If not, your flesh and bones will soon be part of its lair, fixed and unmoving for all eternity. However, if you do carry this out right, you might just gain the wisdom of their kin and bring blessings upon your own.

In the vast realms of long dead stars, they came. No one knows whence, no one knows why, but one thing above all is certain; they are here amongst us. For æons, they have passed in our midst, perhaps even in great numbers, but we could never see them, until they chose to manifest themselves to helpless mortals, whose minds were permanently alienated by the experience, and few survived for long the horror of the gaze. Some things were simply not meant to be known to us.

I started to study this strange new phenomenon, which had recently become a buzz in my Anthropology department, and I, being a graduate student full of curiosity and ambition, was consumed by the idea of finding a new place to study for my doctoral degree. I had pursued both Anthropology and Neuroscience as my undergraduate degrees, so I was considered the right person for this job, someone who would study the increasing levels of apparent madness in a local population in in an ancient area in Greece, without succumbing to the more fanciful explanations of why such a pathology was spreading in the first place. I know better now, but every part of my being wishes I didn't.

Two scholars had been residing there for the past couple of years, both consumed with the idea of studying the place, and each convinced, in their own way, that the local populace possessed some key to understanding something deep and disturbing within humanity itself. Dr. Paul Eckstein was the originator of this study, being by training a classicist and archeologist, possessed with the singular notion that the divine myths of Ancient Greece were, in reality, experiences induced by local drugs, which put people in touch with a door within humanity itself, giving them access to something very much real, and often deeply terrifying, but only because we did not yet comprehend the meaning of it. His colleague, and also fiercest rival, was a Dr. Helena Kingsford, who had discovered in the first Doctor's writings what she considered incontrovertible proof of alien life forms, which had been her passion to prove, ever since her thesis, where she argued that humanity's origin itself was due to intelligent life forms making contact with lowly hominids on our rare, blue planet.

Dr. Eckstein began all of this, by attempting to locate the entrance to Hades, the Greek underworld, convinced that he would find just the right hallucinogenic drugs and the right area to explain these queer and unnatural revelations, that gave humanity great insights, but also the keys to what could be our undoing. Indeed, he found a cave, near the southernmost tip of Mani in Peloponnesos in Greece, not too far from his archeological excavations, with a secluded, tiny village having it as their own sacred spot. Indeed, they seemed untouched by Christianity, for this hamlet had no visible church. They lived apart from humanity, consuming the local mushrooms, and experiencing spectacular visions in their dream states. However, these were not the gentle, spiritual journeys that were associated with Ayuhuasca or DMT, but terrifying plunges into a Hades that had become all too real, experiencing contact with dark entities from beyond the stars, known to them as "the Asterons," named after the word for "star."

The key ingredient to inducing such a dream state was a psilocybin mushroom variant known as "oneiromanteio," or "The dream oracle." Dr. Eckstein related to me early on how the oracles of Antiquity, from Olympia to Delphi, and back to Dodona, who would regularly consume such hallucinogenics to put them in the necessary state to make contact with the gods, which was really an evolutionary step towards humanity understanding its own potential. The potency of the drug was undeniable, and it was easy for skeptical outsiders to simply dismiss the mass delusions as being nothing more than a shared psychosis from excessive drug use. I know that way of thinking only too well, for I was too a skeptic, when this all began.

As one might expect, Dr. Eckstein's work was considered, by most academics, to be an exercise in frivolity, perhaps even an excuse to legally consume psychoactive drugs himself, but he did manage to find a very eager correspondent in Dr. Kingsford, who, despite her great admiration for the study, believed that the explanation for the growing madness lay outside of the local populace and their pharmaceuticals, indeed, outside of our planet, considering instead their beliefs and their mythos to be based on collective memories of which humanity used to be more aware, but had largely forgotten, over the æons. Being a trained astronomer by trade, she had never lost her passion for psychology, being convinced the true explanation for the former inevitably came back to the latter.

I was meant, from the day I arrived, to study the local population, already dwindled in numbers, over the generations, but which had become even more so, over recent years, as more of them had succumbed to madness. Local authourities considered this a case of nothing more than the effects of isolating from their fellow Greeks, along with an overconsumption of psychoactive substances. What these official reports failed to mention, and which I had to catalogue meticulously, was that every person who succumbed to permanent lunacy, from the village, would later on, in the nearest asylum, repeat the same words, over and over, giving no hint of even seeing our world anymore. Their gaze would be darkened, as if set upon another world, and their one experience was summarised with these words:

Indeed, the only time when these poor alienated people acknowledged anything from our world, was when someone nearby uttered these same words, and they would nod along, and frequently start chanting in turn. I had no help in this from my readings on mass psychogenic illness, as no literature seemed to be able to explain why no one ever appeared to be in transition from a state of apparent sanity, to clear and undeniable insanity. Many whom I studied, and indeed befriended, whilst living there, would appear rational, one day, consuming their narcotic of dreams, and trying to make contact in dreams with the stellar entities, and only on the day that the latter appeared to make contact back, would the former find themselves beyond any therapeutic treatment. Indeed, a growing number who experienced it, were so struck by the mind-twisting horror of the experience, that their hearts inevitably gave out, and they would be found dead, staring into the black abysm of their final experience.

I was desperately trying to find a way to prove both Doctors wrong, not for my own selfish, academic reasons, simply to finish my degree, but to hold onto the idea that the world is still a rational place, governed by natural laws, and explicable by science in a way that makes it better. The more I studied these locals, the more I found myself unable to explain the claims that they made, and which both Doctors believed, each in their own way. The only ones who seemed resistent to the growing bouts of madness were a small group of select individuals, about whom there were fanciful claims, claims I never would have entertained as anything other than mere folk lore, because their explanation for this singular ability of retaining basic sanity in the face of meeting these astral travellers was that they were the offspring of mothers who had been alienated from their sanity, from encounters whilst pregnant, and while they had all gone quite mad from the experience, their offspring would be transformed psychically by it.

The children of the pregnant woman to whom this occurred would constitute a group with newfound abilities, the "Dreamwalkers," who could see the glimmering traces in the air of the astral walkers. Like embers of the dying stars in the night sky, the emissaries of madness who travel to us, appearing as normal men, will leave a trace that only those whose minds have been touched by the mad horror of their kind can see outside of a drug-induced state. Only these people are sane enough to communicate the contents of this sidereal vision, in the form of a golden, shimmering wave, a trace of the unknown entities passing through, and intending to make contact. That is how, after untold generations of madness, these people were finally able to glean dark truths from these experiences, and know something of their visitors, be they visitors from distant stars, or from our own deepest, darkest wells, which evolution saw fit to close as an avenue of exploration, but which we keep trying to tear open.

I had to put in many months of work before the locals trusted me enough to even allow me near the nexus of the greatest dread of all, the entrance to their own Hades, the cave known by some as "Alepotrypa," or "the fox hole," which was named after the legendary cunning of the fox, based on their folk lore. However, the kind of cunning they sought was deep, dark revelations of the mind, putting them in touch with the Asterons. Had I known from the start that this was not mere native mythology, I could have avoided all of this, and the mysteries of the cave would have consumed one less soul.

I had only gleaned bits and pieces, up until then, about the bizarre experiences of the locals. Their timidity was no mere shyness, I gathered, but an experience of constant fear that I might be one of their astral visitors, disguised in human form, and they would look deep into my eyes, those gifted enough to spot the presence of these beings, to see if they could see the golden sparks that hinted at what they could see in the dreamworld. This might have been easily dismissed as paranoia, had not such similar results occurred in nearly every person with whom I made acquaintance over there.

Whilst I grew closer to the locals, the number of people who had been touched by insanity grew, sometimes by the day, and the rivalling theories between the two scholars grew into a full-fledged feud, as they grew ever more convinced that the other's erroneous thinking was leading the research astray, and resulting in more forced institutionalisations, as well as more deaths, from those who could not handle the sheer terror of what they saw. As for myself, I could only see two patterns, in terms of who was more at risk; those who were touched with the gift of dream walking could handle much more, and those who partook in too generous a quantity of their local drug, before the ceremonies, they were far more likely to wind up stuck in a nightmare from which they could not awake, so their body would often give out.

By the time I was allowed to go with the few that remained, to observe and follow along in their strange ritual, in the cave, I was already fearful for my life. Of the hundreds I had met when I arrived, only dozens remained, the phenomenon having decimated the local population, and science was not providing me with any of the comfort it had during my earlier days, as an undergraduate student. As I sat observing their chanting rituals and their partaking of the ceremonial hallucinogenics, the oneiromanteio, I wished that the ensuing cloud of smoke could deprive me of my fears, but they remained with me.

Kostas, a youth in his early twenties, provided all with the pre-measured dose, considered most safe, but I could not bring myself to agree to try it, much as I had been curious on my initial arrival. As I pushed it away, eyeing it carefully, the careless youth partook of it in my place, thus doubling his dose. I was about to try to stop him, but an elder grabbed my arm and said: "is okay. He is dream walker. He will learn." Those with this cursed pathology, were considered gifted, I realised, and they were hoping that with the right communication, they would find out how to save themselves from the soul-sucking terror and deaths that were plaguing their village. I had thought they sought enlightenment, they way we pursued science and knowledge, but in reality, it was about survival, with the dream walkers being a next step in a Darwinian process. I could not help but think that this seemed, if anything, to be a truly unnatural selection.

The huddled congregation descended into their Hades, seeking answers from the gods of the netherworld, but despite the unique ability of of the locals of knowing how to open those portals, none yet knew how to close them. The howls of desperation, of fear, and of eyes staring into the blackness of space, accompanied by the twitching of their bodies, became a sight so familiar that I was almost unmoved by it, after a while. Then came a piercing shriek from Kostas himself, the youth considered the most gifted of all the dream walkers.

As the trances wore off for the regulars, Kostas was still trapped. I curse myself for allowing him that second dose. I don't know what was more terrifying, on that day, hearing the cries of abysmal terror from this youth, along with his uncontrolled seizures, or seeing how his family tried to bring him back, to make him see them again, but his eyes could no longer see this realm, though those family members were but inches away. Nearby were also the two Doctors, desperately calling for the youth's attention, but to no avail.

I finally managed to get near to him, and right at that moment, his body tensed up, his jaw slowly dropped, and his eyes twitched, but his eyelids never fully closed. He murmured the words: "I see," before a final gasp was heard, and then, his body gradually grew colder, as his psyche expired. His family did not exhibit any hysterical behaviour; in fact, they hardly expressed a tear, for this was the life they knew, the only life any of them knew. An elder, his grandfather, closed Kostas' eyelids, and uttered a prayer for him. As they took it in stride, I, along with the Doctors, was shaken to my very core.

After this event, things changed rapidly for us scientists. No one was interested in talking to me, but instead, the Doctors quarrelled incessantly about their theories, depriving me of sleep night after night, until one night arrived, when they finally fell silent. At first, I thought I would get proper sleep at last, but I was quite mistaken. As soon as I had entered the first somewhat gentle sleep I had had for months, I heard a loud shriek from the tent the Doctors usually stayed in. I awoke abruptly, but rather than the scream ceasing, it continued, and another distinct scream followed it, as if competing for the attention of my ears. I ran over to the tent.

What I saw, will haunt me for the remainder of my days on this planet that the stellar entities chose to visit, and perhaps more. Both Doctors were deep in an astral trance, staring into the distance, clearly having consumed an exceptional amount of the oracular stimulant. In their pursuit to finally reveal the source of the Asterons, internal or external, they had taken the final leap, through overconsumption, and now, they were trapped in the darkest recesses of their minds, whence there was no escape.

Dr. Kingsford was babbling incoherently, whilst seizing violently, and Dr. Eckstein was already in the throes of his heart giving out, and no mere attempt at revival was able to accomplish anything. Just like with Kostas, the tragic youth who died in the cave, he could not be saved, only this time, I was right next to him, with no one blocking the way. As his body became pale and rigid, and the breath of life left him, I looked into his eyes, for an account of what his lips had been unable to speak of.

His eyes had drunk deep of the abyss from beyond the stars, taking in the sight that most mortals are denied, or rather, spared. What he did not anticipate, was that the abyss had also gazed back into him, locking his gaze, sending the last shreds of his sanity into the void, and his heart had failed him, as he had fallen down to the floor. His dead eyes seemed like a portal to a nether realm man was never meant to know, just before I closed his eyes.

I was called from a state of tragic inaction by a final, violent seizure from Dr. Kingsford, who uttered the tragic words that all alienated victims seemed to know by heart: "From the Æther, and the dying star, the Asterons take flight in dreams. They travel bringing madness from afar, and nothing is what it seems." Those were the last words from Helen, but not her final communication to me.

As I gazed into her eyes, seeing the same portal to terror that had proven fatal to Dr. Eckstein, I saw a distinct, glimmering wave, as if I was looking into the dream world of the Dreamwalkers, and seeing the traces of the Asterons. Until then, I had only heard these visions described in reports, and I recoiled in horror, because this revelation would now mean that I also would be gifted in such a way, and able to be contacted by the terror from outer space, like the curse that had passed from generations inside this place.

I fled the village, never to return, either to it, or to my studies, seeking only to avoid meeting the same fate as my two guides. Sleep has become a rare commodity, as of late, in the knowledge that dreams is where the Asterons can find me. As I gaze up at the stars, on many a night, I still see occasionally the shimmering waves, golden terror that is invisible to others, and I cannot help but think of one terrifying prospect; are the stars also looking back at me?

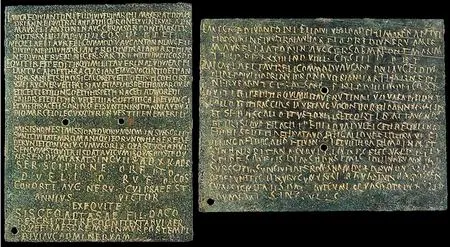

Edward Gibbon (1737-1794)

The most famous work ever on the subject of how Rome fell is without a doubt Edward Gibbon's "The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire," a six-volume work whose individual parts were published between 1776 and 1789. In this monumental work, this Enlightenment historian makes numerous claims about the decline and fall of this great empire, not all of which stand up to scrutiny, but most interestingly, he presents two very different tales. Without further ado, let's get into it:

"The story of its ruin is simple and obvious; and, instead of inquiring why the Roman empire was destroyed, we should rather be surprised that it had subsisted so long. The victorious legions, who, in distant wars, acquired the vices of strangers and mercenaries, first oppressed the freedom of the republic, and afterwards violated the majesty of the purple. The emperors, anxious for their personal safety and the public peace, were reduced to the base expedient of corrupting the discipline which rendered them alike formidable to their sovereign and to the enemy; the vigour of the military government was relaxed, and finally dissolved, by the partial institutions of Constantine; and the Roman world was overwhelmed by a deluge of Barbarians."

- Chapter 38 "General Observations on the Fall of the Roman Empire in the West"

The decline and fall of the Roman Empire(1776-1789)

Here we have a classical view in its nutshell; invincible barbarian hordes of invaders brought down the once-mighty Empire, which had been corrupted from within by adopting the ways of foreigners, and bad men had succumbed to corruption, becoming unfit leaders. This we might call the conservative claim, since it basically makes the case that one must be wary of foreign influence and have a strong, standing army, ready to repel barbarian hordes. However, lest you think him a Conservative (which would have been a Tory at the time), in the true sense of the word, he was quite Progressive, joining with the secular spirit of the times of seeing Christianity as the enemy, and Catholicism in particular. His most famous quote from this work is, after all, the following:

"The various modes of worship which prevailed in the Roman world were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosopher as equally false; and by the magistrate as equally useful."

- Chapter 2: "The Internal Prosperity in the Age of the Antonines, part I," section I

To be fair, he does not consider Christianity in itself the cause for the downfall, but rather, that it precipitated the fall of the Empire, once it entered into its corruption phase, after the rule of the "good emperors," which were the emperors between Augustus (proclaimed in 27 B.C.) and Marcus Aurelius (end of rule 180 A.D.). Gibbon lays this case out in detail:

As the happiness of a future life is the great object of religion, we may hear without surprise or scandal that the introduction, or at least the abuse of Christianity, had some influence on the decline and fall of the Roman empire. The clergy successfully preached the doctrines of patience and pusillanimity; the active virtues of society were discouraged; and the last remains of military spirit were buried in the cloister: a large portion of public and private wealth was consecrated to the specious demands of charity and devotion; and the soldiers' pay was lavished on the useless multitudes of both sexes who could only plead the merits of abstinence and chastity. Faith, zeal, curiosity, and

more earthly passions of malice and ambition, kindled the flame of theological discord; the church, and even the state, were distracted by religious factions, whose conflicts were sometimes bloody and always implacable; the attention of the emperors was diverted from camps to synods; the Roman world was oppressed by a new species of tyranny; and the persecuted sects became the secret enemies of their country. Yet party-spirit, however pernicious or absurd, is a principle of union as well as of dissension. The bishops, from eighteen hundred pulpits, inculcated the duty of passive obedience to a lawful and orthodox sovereign; their frequent assemblies and perpetual correspondence maintained the communion of distant churches; and the benevolent temper of the Gospel was strengthened, though confirmed, by the spiritual alliance of the Catholics. The sacred indolence of the monks was devoutly embraced by a servile and effeminate age; but if superstition had not afforded a decent retreat, the same vices would have tempted the unworthy Romans to desert, from baser motives, the standard of the republic. Religious precepts are easily obeyed which indulge and sanctify the natural inclinations of their votaries; but the pure and genuine influence of Christianity may be traced in its beneficial, though imperfect, effects on the barbarian proselytes of the North. If the decline of the Roman empire was hastened by the conversion of Constantine, his victorious religion broke the violence of the fall, and mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors.

- "General Observations On The Fall Of The Roman Empire In The West"

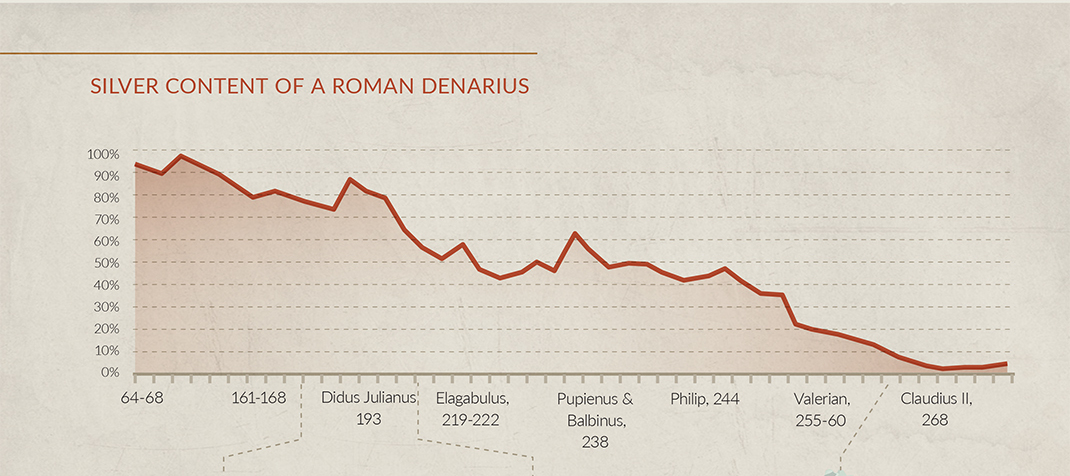

Thus, what we see in Gibbon is not one, but two tales, though they do dovetail (pun intended) into one basic claim; Christianity helped weaken the State (which Progressives love to claim and that is why we will refer to at as "the Progressive theory"), and actually spread corruption, despite its attempts to curtail such activities, and discouraged people from pursuing the earthly interests of the State and of the people. There is no need to point out that Christianity had massive schisms early on, or that Rome clearly suffered an identity crisis, as Christianity took over, but I believe Gibbon is actually missing much here, not due to a lack of scholarship, or due to a lack of attention to detail, but due to him not knowing about evolution, and how that affected us, as well as not knowing certain economic facts, or how to calculate probabilities, given these facts. He was, after all, a man of his time. We need to evaluate the likelihood of these claims, which anyone can do. However, to do so, we must go to the very beginning, to the founding of the Empire, to understand what it was that finally fell, and thus, to evaluate how it fell.

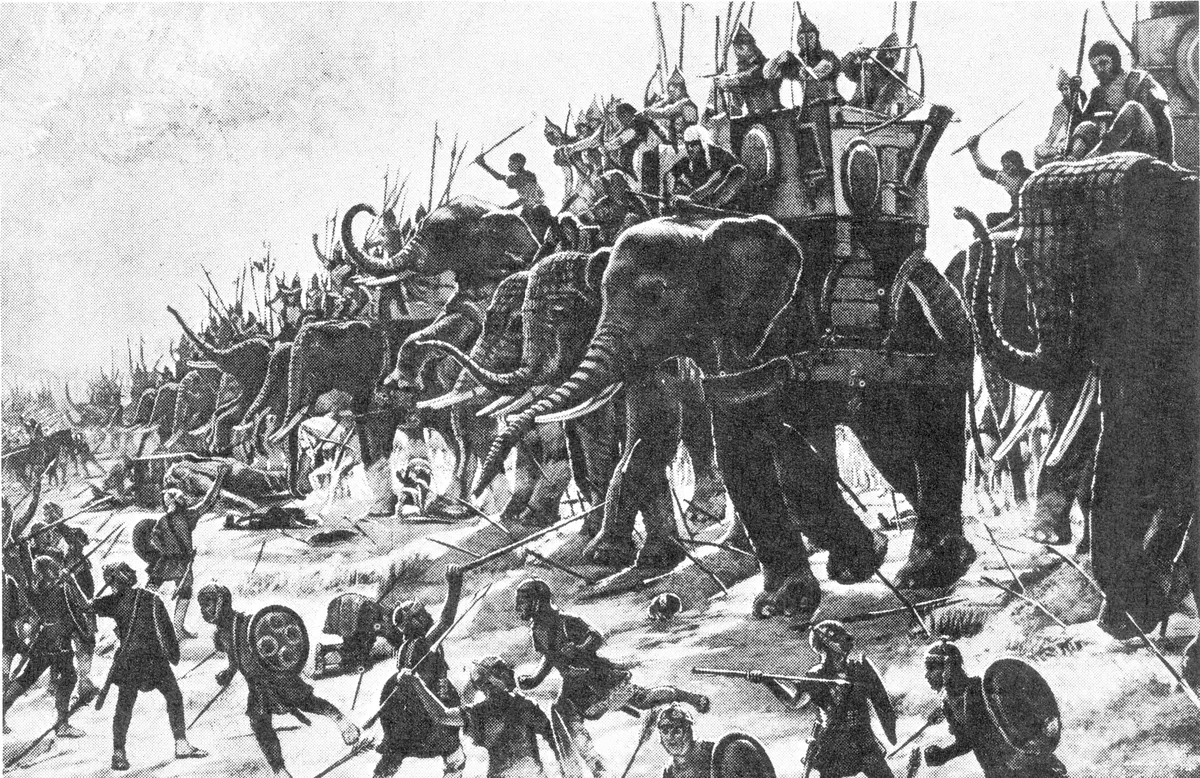

In the late 1st century B.C., Rome was reeling from a long and bloody civil war that had claimed many of its citizens. A triumvirate, that is, a rule of three men had been established in 43 B.C., following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., who had in turn won out over his rivals in a previous triumvirate, and proclaimed himself dictator of all of Rome in 49 B.C. The final triumvirate was an accord between three potentates: Gaius Octavius, the named heir to and adopted son of Julius Caesar, from a wealthy family, Marcus Antonius (usually referred to as "Mark Antony"), a politician and general who had fought with Julius Caesar, and also the lover of Cleopatra (something which he had also inherited from Julius Caesar), and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, an influential general and holder of the prestigious title of Pontifex Maximus, or head priest (that's where we get words like "pontiff" or "pontificate").

The battle of Actium 31 B.C.

This internal power struggle could not be avoided, much like in the first triumvirate between Julius Caesar and his rivals. Lepidus was stripped of his titles by the increasingly powerful and influential Octavius, and after his troops had defected to the latter's service, Lepidus was forced to live the rest of his life in exile. As for Marcus Antonius, he was defeated at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C., then any possible future in Egypt was crushed in 30 B.C., as Octavius' forces put down the forces in Alexandria. Marcus Antonius and Cleopatra famously committed suicide together, thus ending both the triumvirate in Rome, and the very last ruler of the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt. Octavius was to be ruler of all Rome, but not just that; he would attain a height that previous dictators, like Julius Caesar, had never attained.

Gaius Octavius Thurinus (63 B.C.-14 A.D.), renamed "Augustus"

On January 16th 27 B.C. the Senate of Rome bestowed upon Octavius the titles of "Augustus" and "Princeps."" The former basically means "illustrious" or "magnificent," and the latter is a priestly title, meaning basically "first in line." Both titles were religious titles, thus wedding the State to religion. Augustus wanted specifically connotations of propriety and of higher truth. Julius Caesar, his deified adopted father, to whom he was heir, was someone he deeply admired, and his victory procession, known as a "triumph," had left a deep mark on him as a younger man.

Julius Caesar's procession of triumph

A triumph is a procession that starts at the Porta Triumphalis, or "Gate of Triumph," then proceeds to the Campus Martius, which was "the Field of Mars," the God or War, a field which had been dedicated to the God of War as the Romans had driven out the last Etruscan King in the 6th century B.C., and then went along the Via Sacra, or "Sacred Way," and finally to the temple of Jupiter, King of the Gods, on Capitoline Hill. A true conqueror was clad in purple robes, on a chariot pulled by four horses, and he received an ovatio, or "ovation" from the people cheering him on, as he rode triumphantly through the streets, distributing various loot and plunder to the people, in a display of supposed magnanimity. Julius Caesar had done this in 46 B.C., with an ivory sceptre, a laurel branch, and a laurel wreath on his head, with a slave behind him, holding a golden crown. He had also seen fit to redistribute quite a lot of loot from the patrician class, which he proceeded to give to the people, which is both why he was popular with the people, and why he was eventually assassinated.

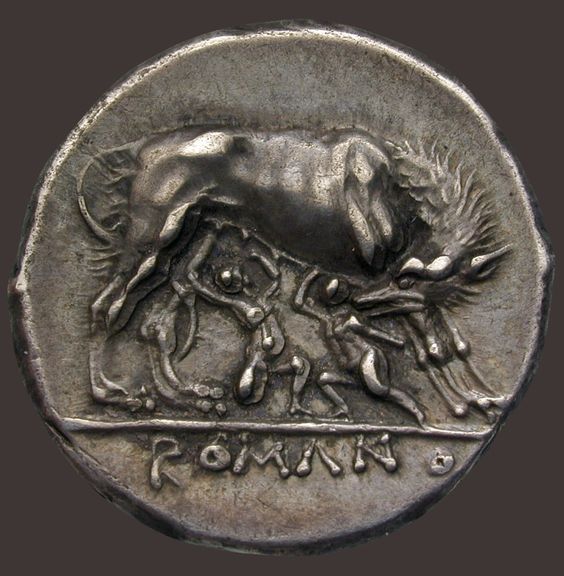

Remus, Romulus, and Rhea Silvia

Romulus, the original title of Augustus, was a reference going back to the very founding of Rome. Romulus was the very first king of Rome, who had been born with a twin brother, Remus, in the 8th century B.C., with their mother being a vestal virgin (at least up until the key point) by the name of Rhea Silvia, and Mars, the God of War (or in some alternative versions, of Hercules, the great hero and monster slayer). Vesta was the Goddess of home and hearth and the purity of vestal virgins had to be protected (of course, gods could always do what they like). The boys were suckled by a she-wolf named Lupa, strengthening them further (similar to stories of how the infant Zeus was suckled by the she-goat Amalthea, whose milk strengthened him). In the end, Romulus and Remus became kings together, but quarrelled, and Romulus slew his twin brother, to maintain his new kingdom. Romulus, not Remus, would survive as the symbol of rule, of strength, of dominion, and Romans would calculate their own calendar based on his rule; this was called ab urbe condita, or "from the founding of the city," and this legend is most famously retold in a work by that exact title by the historian Livius, or "Livy" in most English sources (64/59 B.C.-12/17 A.D.).

Atia, mother of Emperor Augustus

It almost seems facile as an explanation, and yet, so much of understanding the nature of the Roman Empire comes from understanding how the first Emperor rose to power, and what shaped him, which, in his case, seems rather obvious, given the two major influences. The first was his mother, Atia (85-43 B.C.), who was also the niece of Gaius Julius Caesar (100 B.C.-44 B.C.), which established a link by blood, before the future Emperor was adopted as his heir. Her character is well captured by the historian Tacitus (56-120 A.D.):

In her presence no base word could be uttered without grave offence, and no wrong deed done. Religiously and with the utmost delicacy she regulated not only the serious tasks of her youthful charges, but also their recreations and their games.

- Dialogus de Oratoribus ("Dialogue on Rhetoric")

Atia was indeed well known in the days of the Roman Republic for her strong, moralistic convictions, and when her husband, Octavius, who was the biological father and namesake of the future emperor, had died, she had remarried instantly, most likely to avoid any appearance of impropriety; she was from a wealthy family, after all, so she did not lack resources, and no mention is ever made of an emotional connection between her and her second husband. The son would form neither a strong bond with his biological father, who had died when he was four years of age, nor with his stepfather (much like his mother), but he would see how his mother needed protection for the constant unrest in Rome. We now turn our attention to the description of his birth, given by the historian Suetonius (69-122 A.D.):

When Atia had come in the middle of the night to the solemn service of Apollo, she had her litter set down in the temple and fell asleep, while the rest of the matrons also slept. On a sudden a serpent glided up to her and shortly went away. When she awoke, she purified herself, as if after the embraces of her husband, and at once there appeared on her body a mark in colours like a serpent, and she could never get rid of it; so that presently she ceased ever to go to the public baths. In the tenth month after that Augustus was born and was therefore regarded as the son of Apollo. Atia too, before she gave him birth, dreamed that her vitals were borne up to the stars and spread over the whole extent of land and sea, while Octavius dreamed that the sun rose from Atia's womb.

- De Vita Caesarum 94.4 ("On the Lives of the Caesars")

Emperor Augustus

Apollo was the God of prophecy, and thus, this story is a hint of prophetic dreams of greatness. Now, we may scoff at this as being an obvious retelling of history to cast Augustus and his mother as the heroes of the past, more than a century later (and it certainly was), but it does more than merely convey a vision; it conveys Atia's obsession with cleanliness and purification, which is confirmed elsewhere, and which clearly did get passed on to her child. It also frames the whole new realm, the new vision, the new Rome as proceeding maternally from female power, rather than male. The legendary founders of Romulus and Remus had, after all, been suckled by a she-wolf, and Atia would be the she-wolf of this new Rome.

Vercingetorix surrendering to Julius Caesar

Now, it is true that the second person was indeed a male, the surrogate father in his life, essentially, and that person was Gaius Julius Caesar, who provided him with a sense of what a man should do. He had conquered much of Gaul, bringing home their great king, Vercingetorix, who had been publically executed, and he had also shown he was a greater military genius than even his former teacher and co-ruler, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, or "Pompey the Great" (106-48 B.C.), by defeating his forces on the battlefield. According to the Greek historian Appian of Alexandria (ca. 95-165 A.D.), when Caesar came before the Senate to report on his war against Pharnaces II, King of Pontus, in 47 B.C., he summarised it pithily thus: veni, vidi, vici, or "I came, I saw, I conquered." Suetonius elaborates further:

In his Pontic triumph he displayed among the show-pieces of the procession an inscription of but three words, "I came, I saw, I conquered," not indicating the events of the war, as the others did, but the speed with which it was finished.

- De Vita Caesarum 37.2 ("On the Lives of the Caesars")

Augustus, however, was not a great warrior, or even a very apt general. He was a thinker, a planner, a man of learning, but clearly wishing he was as great as Julius Caesar had been. However, if he surrounded himself with the cream of the crop of military might, and increased the power and funding of the military, he could be an even greater ruler than Caesar, and that is exactly what he did. He would get others to carry out the orders, while he fashioned the new Rome into his image, a place where Atia and all other women could be safe from the threats of barbarians and immoral dissidents.

Though militarism is considered traditionally a masculine quality, indeed, a masculine flaw, it is anything but this, if you think about it. Yes, it is men that go to war, yes, it is men who typically find the reasons to go to war, but why do they go to war? To gather resources for their women and children, and if attacked, to protect those same people. Find me a war where the justification for it was to protect its male population and I will find you a unicorn. As for the influence of women, consider the wife of Augustus, initially known as Livia Drusilla (59 B.C.-29 A.D.). Described as modest and chaste in the extreme by historians, her lifestyle quickly changed, once her husband died, and their son Tiberius became the new emperor; she was known as mater patriae, or "mother to the fatherland," to the Senate, and was renamed Julia Augusta, to essentially give her the former emperor's title. She would, like so many other women of influence, rule behind the curtains. After all, if you can get decisions made, and not be the subject of violence or assassinations (Augustus was possibly poisoned by Livia herself), all the better.

Rome, like any great city, started with militiae to defend it, and occasionally, to attack others. This is how the history of mankind has played out; we have taken each other's resources by force, until it was discovered that allowing others to produce more resources, while we worked on ours, and trading freely, actually gathered more resources for both. However, this is not how people thought during most of Antiquity; even the concept of empire, allowing others to live under subjugation whilst paying taxes as second-class citizens, was considered a means to create peace and prosperity. Gaius Marius (157-86 B.C.), the great general, had been the first to create a standing army, a State-run army, paid for by taxes, about a century prior to this, and after that had followed Sulla the dictator (138-78 B.C.), then the two triumvirates mentioned above. With a standing state army, rather than militiae to call upon when needed, they had to serve the State machine 24/7, which was a major cause in the downfall of the Republic. Generals made war on other generals, as well as other leaders, until Augustus triumphed over all.

Augustus imposed a moral vision on society, one clearly derived from his childhood, and imprinted by his mother, to a large extent, as well as by Julius Caesar's legacy. The way to protect women would be through a great, standing army, and to make sure to impose a system to incentivise marriage and punish the grievous sin of bachelorhood. As the Italian historian Guglielmo Ferrero (1871-1942) puts it:

"He (Augustus) devised an ingenious system of rewards and penalties to overcome the selfishness of bachelors; there were to be rewarded for the

responsibilities and cares inseparable from marriage, and penalties to outweigh the obvious conveniences of celibacy"

- The greatness and decline of Rome Vol. 5, pp. 60-1

Why would the Emperor react so harshly against this, were it not for the fact that this would leave the women of Roman society unserved? Men, left to their own devices, pursuing their own goals, whether with drinking or with philosophy, did not provide any use for society, which is to be measured by their adherence to State ideology, their protection of women and children, and their fathering of many children, in a State that was seeing declining birth rates. On the subject of the last point, it never seemed to occur to the writers of the time that maybe the continual wars had a little something to do with it, killing many local men, as well as requiring them to live far away, most of the time, or that men were avoiding marriage in greater numbers precisely because the legal system was making it a less favourable proposition for them.

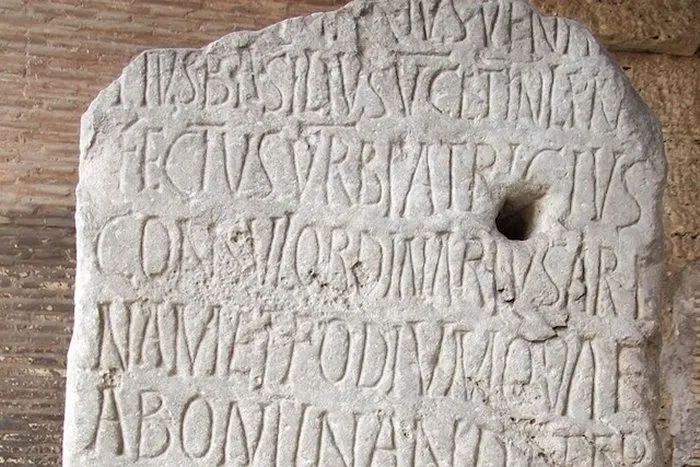

Lucius Cassius Dio (155-ca. 235)

In his monumental work on Roman history, historian Lucius Cassius Dio (ca. 155-ca. 235) wrote of Emperor Augustus separating the Roman aristocracy into married men and unmarried men. The married men were “much fewer in number.” On the one hand, Augustus praises the men who have married, because they have been true to their fatherland, to their ancestors, and have continued their class. However, the unmarried men received a blunt and harsh criticism:

O — what shall I call you? Men? But you are not performing any of the offices of men. Citizens? But for all that you are doing, the city is perishing. Romans? But you are undertaking to blot out this name altogether.... You talk, indeed, about this ‘free’ and ‘untrammelled’ life that you have adopted, without wives and without children; but you are not a whit better than brigands or the most savage of beasts. For surely it is not your delight in a solitary existence that leads you to live without wives, nor is there one of you who either eats alone or sleeps alone; no, what you want is to have full liberty for wantonness and licentiousness.

- Historia Romana Liber LVI.10

("Roman History", Book LVI.10)

If this strikes the reader as patriarchal, it is worth asking why it seems that way. Augustus is one man, representing a tiny élite of both men and women, and his prescriptions and condemnations are universally reserved for men. Nowhere, in any of these laws, is anything prescribed for women, in terms of punishment, and nowhere is the fact that fewer are getting married described as being even partially on women, even though these were not forced marriages. It may be objected that women were relegated to the home, meant to be merely mothers and wives and to have no further ambitions. Well, for nearly all of the men in Rome (or elsewhere, for that matter), the situation is no better for the men; they must provide, and they will go where the means of provision lie, which is increasingly found in the military, whether they want to or not. If you had a choice, would you rather be forced to leave your home, occupy a foreign land, risking being killed, while your wages were sent to your family, rather than for your own selfish pleasures, or stay at home, taking care of your children, whilst being the recipient of such largesse and protection? There has never been a society where men in large numbers even hoped for the latter, and clearly, leaders are aware of it, when they give their speeches.

Not only were the limitations universally prescribed for men, but great moral leniency was shown to the women of Rome. Faustina the Younger (130-175) cheated on her husband, the emperor Marcus Aurelius (121-180) constantly, having a particular fondness for gladiators, an occupation which would not have existed, were it not for the consistently female audiences who found arousal in these bad boys and even more so when blood was shed for them (detailed in works such as the Satyricon by Gaius Petronius), and this definitely had a greater amorous effect on her than her husband, who was the embodiment of Stoic philosophy, preferring to live a life of virtue. He was even asked to denounce her sordid affairs, but would only quip Stoically: "if I send away my wife, I must also repudiate her dowry." He still saw it as his duty to care for her, regardless of her indiscretions, and abandoning that would mean abandoning his duties as a man.

This must be distinctly understood, as a fact about humanity itself, if we are to understand why the Roman Empire fell. While laws were enacted under Augustus that seemed to ordain marriage and punish adultery for both sexes equally, our natural instincts can never be denied, and men are programmed to care more for women. Hence a woman in exile from Rome can and was often cared for by her family, or by a new husband, whereas a man in exile had to fend for himself. Even the gender-neutral theory of these laws soon fell out of use, as women of influence in the empire found them needlessly repressive, and they made sure their male relatives in office voted the right way. This culture would carry over, many centuries later, into maffia families, where the wives would be pulling the strings to make sure order was maintained, and their interests were served, just like the upper crust women of Rome made sure their interests were served. However, even lower-class women were served by these protections, as their male relatives were bound into a servitude that came at a greater personal cost to them.

Valeria Messalina (ca. 17/20–48)

As an example of this female selection of the appropriate dynasty, and of power behind the scenes, we have but to turn to Valeria Messalina (ca. 17/20-48), wife to the fourth emperor, the emperor Claudius (10 B.C.-54 A.D.), and also sister to the third emperor, Caligula (12-41 A.D.), who formed an influential clique of the most important men in the imperial court to secure her powerful position and influence. She freely slept around to gain favours from the men around her, all the while accusing others of the very adultery she was committing (including her own niece, Julia Livia), and ordered the poisoning of Marcus Vinicius, an influential consul. "Whenever they desired to obtain anyone's death, they would terrify Claudius and, as a result, would be allowed to do anything they chose," Cassius Dio reports in "Roman History".

After the birth of Messalina's son, Brittanicus, she used her influence to remove any rival claimants to the imperial throne, Paul Chrystal wrote in his "Emperors of Rome: the Monsters" (Pen and Sword Military, 2019). "The first to go was Pompeius Magnus (A.D. 30-47), the husband of Claudius's daughter Antonia, who was stabbed while in bed." Messalina was cruel, no doubt, but she was also part of the system that had been established. Even when it was obvious that she was lying, and committing the very offences she was accusing others of, she was given more credence than her male counterparts, and criticism of her was far more difficult. In the end, she was condemned, partly because she was trying to overthrow the emperor, but not before she had done much damage, and, refusing to commit suicide, in the Roman way, she was run through with a sword.

Agrippina the Younger (15-59 A.D.)

For that matter, let ust take the example of the first Empress, Agrippina the Younger (15-59 A.D.). She was the younger sister of Caligula, who had ruled before Claudius. In 39 A.D., her brother, Emperor Caligula (12-41 A.D.), exiled her for plotting against him, but she returned to Rome after he was assassinated in 41 A.D. Eight years later, she married her uncle, Emperor Claudius. The emperor even changed the laws surrounding incest in order to marry his niece, who wielded a great amount of control over her new husband. He was either unwilling or unable to do anything about her plotting, though he was clearly aware of it. At his death in 54 A.D., she took over as the new empress of Rome, over her son Nero, which was quite the feat, given that she was highly suspected of having poisoned her husband. Nero eventually inherited it upon her death in 59 A.D. This clearly shows women were just as capable as men of doing great evil, and there was much evil early on, in the very first imperial dynasty. To this day, we know the advantage of having female politicians, because we refuse to accept that they can be every bit as evil as the male ones.

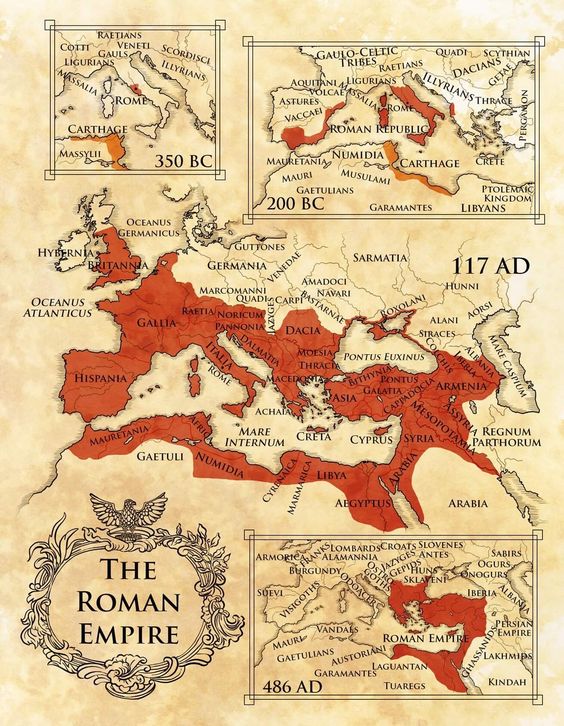

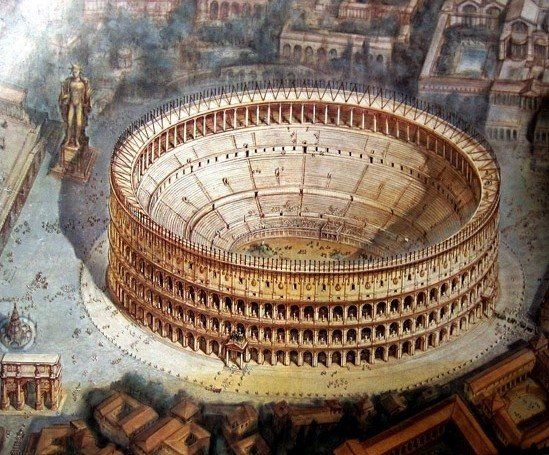

The Roman Empire

Rome had been facing a question ever since its inception, namely, what its own culture was. Rome had deposed of Etruscan kings, but its origin tales, its mythology, and even much of its literature were borrowed from the Greeks. Indeed, its Gods were nearly all Greek Gods, conveniently given new names, but filling mostly the same functions; Ares, God of War, became Mars (whence comes the adjective "martial," referring to war or combat), Zeus, the Sky Father and Lord of Olympus, became Jupiter (whence comes the expression "by Jove" and also "jovial"), Poseidon, Lord of the Ocean, became Neptune, and so on. The only God who kept his exact name was Apollo, God of reason, mathematics, harmony, and prophecy. Educated Romans usually spoke Greek, and east of the Italian peninsula, Greek was the everyday language. In addition, all the schools of philosophy were Greek, from the Stoics, to the Epicureans, to the Cynics, to the Skeptics, to the Pythagoreans, not to mention Platonists and Aristotelians (there is no need to go into the actual philosophies here, merely to enumerate them).

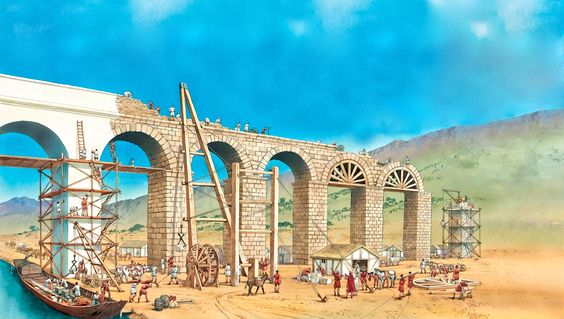

"Construction of an aqueduct" by Peter Dennis

The question had been asked before; what exactly was Roman culture? There seemed to be a danger of Romans being merely Greeks living in a different part of the world, even if they were better at applying Greek theory into working inventions, such as aqueducts and sewers, both quite necessary to civilisation, and both being Greek ideas, but far less successfully implemented by Greeks. Romans were also better at building lasting architecture, roads, and bridges, all impressive and practical, yes, but what was the use of it, if there was no sense of what a Roman was really all about?

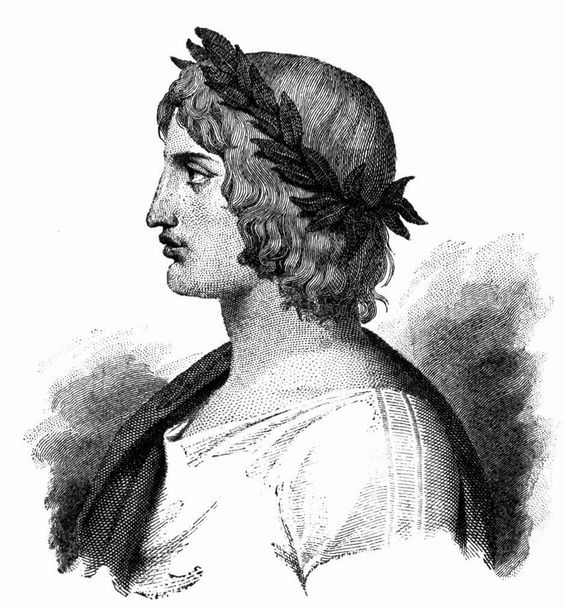

Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.)

Possibly the greatest writer in all of Rome's history, Publius Vergilius Maro (70-19 B.C.), known more commonly as "Virgil," coined a phrase to reflect this attitude which captured a perhaps warranted mistrust of the Greeks, in 29 B.C., right after August had been proclaimed Emperor: "Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes," ("the Aeneid," book II, line 49) meaning "I fear the Danaans[Greeks] even when they come bearing gifts." The context for this memorable phrase was in the context of the fabled Trojan War, when the mainland Greeks had won in the end by hiding their soldiers inside of a giant wooden horse, which, after being admitted into the city, allowed their soldiers to sneak out, open the gates to the city, and all of Troy was conquered, plundered, and set to the torch. While warranted by the context of the story, it also seems unlikely that Virgil was not also appealing to a growing sense of Rome needing its own culture, and to the newly minted leader to help guide them there.

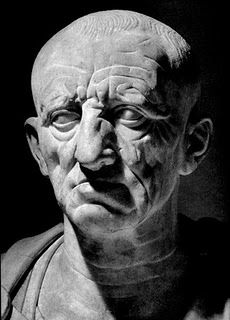

Cato the Elder (243-149 B.C.)

The Greeks had indeed brought great cultural gifts to Rome, but some mistrust was certainly warranted, especially if Augustus was to realise his vision of a truly great Rome, a shining city of marble and perfection. Such an empire must have an identity of its own, a coherent narrative, where Romans did not just copy the ways of the Greeks, and where the bad habits of bachelorhood was seen as their corrupting foreign influence. Some more extreme versions of anti-Hellenism also existed, most notably expressed by the senator and historian Cato the Elder (243-149 B.C.), and recorded by Pliny the Elder (23/24-79 A.D.), famous naturalist, thinker, and personal friend to emperor Vespasian (9-79 A.D.):

Concerning those Greeks, my son Marcus, I will speak to you more at length on a more appropriate occasion. I will show you the results of my own experience at Athens, and that, while it is a good plan to delve into their literature, it is not worthwhile to make a thorough acquaintance with it. They are a most iniquitous and intractable race, and you may take my word as the word of a prophet, when I tell you, that whenever that nation shall bestow its literature upon Rome it will soil everything; and that all the sooner, if it sends its physicians among us. They have conspired among themselves to murder all barbarians with their medicine; a profession which they exercise for gain, in order that they may win our confidence, and do away with us all the more easily. They frequently label us "barbarians," and stigmatise us beyond all other nations, by giving us the abominable appellation of Opici. I forbid you to have anything to do with physicians.

- Naturalis Historia Liber XXIX.7

("Natural History", Book XXIX, chapter 7, own translation)

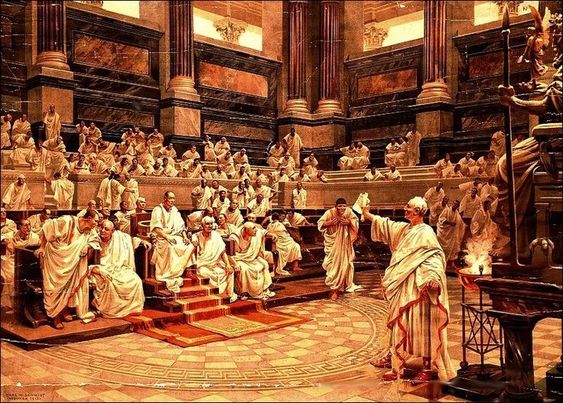

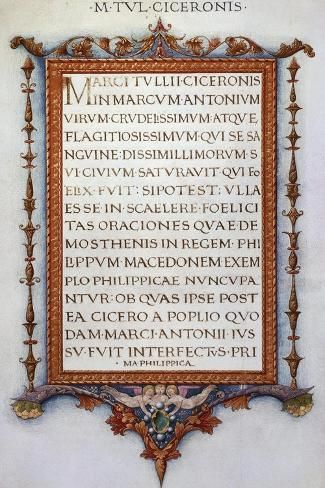

Cicero before the Senate

A more nuanced approach, as well as a more useful approach to Augustus, came from someone who was the closest Rome had to a philosopher of their own, a patrician statesman, lawyer, and scholar by the name of Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 B.C.), who had studied Skeptic and Stoic philosophy. He had paid the heaviest price of all for daring to defend the Republic. He had initially joined the liberatores ("liberators" similar to our expression "freedom fighters") who slew Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., then had opposed the following triumvirate, Marcus Antonius in particular, because that rule sought to undo what little republicanism remained. He was marked for death by the rulers the next year for this criticism of the State (though Augustus himself had allegedly appealed for some clemency, probably because he knew he himself would have to fight Marcus Antonius one day), and soldiers came to sever his head from his neck, and bring it back as a sign of duty carried out. He willingly complied.

It may seem odd for someone like Augustus to seek clemency for Cicero, and even stranger that he would become a writer venerated by the future Emperor, but it actually makes sense, once you get into what Cicero represented, and not just his enormous popularity and influence in Rome. For one thing, Cicero had defended the Stoic idea that there is a natural hierarchy, an inborn order to things, which for him would be reflected in the legal system: “Philosophy helps men understand themselves and their place in the Natural Order of the world” ("Laws," book I). To this, he adds: “The good life is impossible without a good state; and there is no greater blessing than a well-ordered state." The Stoics had been rather vague and religious about their ideas of a divine order, but Cicero made it clear that order, as we see it, would come through a State governed by enlightened, critical thinkers, the novus homo, or "new man."

Roman Coin with "Pax Augusta," meaning

"The Peace of Augustus", i.e. the Roman Peace

This fit Augustus like a glove. People would soon forget that Cicero was actually warning against the dangers of a tyrant, as long as the blessings flowed from the new State, the one that would provide them with a good life, with order, with security, and where peace would be maintained. Tyrants of all ages have always needed intellectuals to justify their régime, while at the same time being highly distrustful of them, since they may spread unwanted skepticism and criticism. Luckily for Augustus, Cicero was already dead, so he could not clear his name. This was to be known as the era of Pax Romana, or "the Roman peace." Many people, Edward Gibbon included, would look to this period as an ideal period of peace and prosperity. It did have its merits, no doubt, but peace came at a heavy price. You could not have this peace without bending the knee, and also, without censoring, exiling, or even killing dissenters, or those who spread licentious writings, or doing away with whatever did not fit the new régime.

Augustus had declared himself pontifex maximus, basically the high priest of Rome, uniting religion and State into one entity to rule over all. He brought a campaign of nationalistic and patriotic values, wherein Roman children would learn to venerate the State, and appointed official censores, whence we get the word "censor," who would review literature for seditious or immoral values. The love poet Ovid would have to spend much of his life in exile for his raunchy descriptions of licentious acts. The very word "censor" actually derives from the Latin word "censeo," which means "I think" in the sense of "I consider." In other words, they were State-appointed officials whose job it was to give the final verdict on whether or not a work of literature was acceptable or not (sound familiar?).

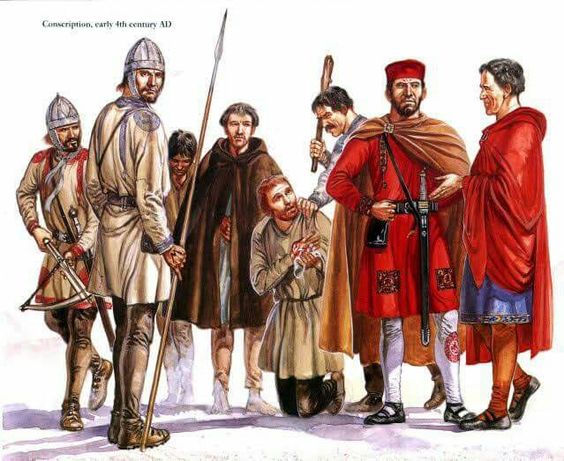

Rights and responsibilities of Roman citizens